Unpacking Ed Sheeran’s Thinking Out Loud case

Storyline

Issue of the Case

The central issue in this case was whether Thinking Out Loud copied Let’s Get It On.

This case has received significant media and blog coverage, but not all reports have addressed the key point. The critical factor here is that the copyright protection for Let’s Get It On is limited to its 1973 deposit copy, which is the sheet music only. Marvin Gaye’s sound recording is not part of the copyright. We, as lay listeners, when interested in this case, might simply search for these two songs, listen to them, and compare. We may find Marvin Gaye’s recording similar to Thinking Out Loud. Surprisingly, this doesn’t matter for the case because, on 24 March 2020, the court established in a court order that the recording was not filed with the Copyright Office and is not admissible as evidence. The comparison is limited to the sheet music of Let’s Get It On and computer-generated audio version versus the sheet music and recording of Thinking Out Loud. I am sure it would not affect it being a fair trial, but it doesn’t feel like a fair duel from a natural justice perspective. If I were the plaintiff, I would probably drop the case there, as the odds of winning are not in my favour. But as lawyers, we can only explain and analyse the situation to the client – the final decision on whether to proceed with the case lies with them, unless conflicts or other legal requirements arise.

Background on the Deposit Copy

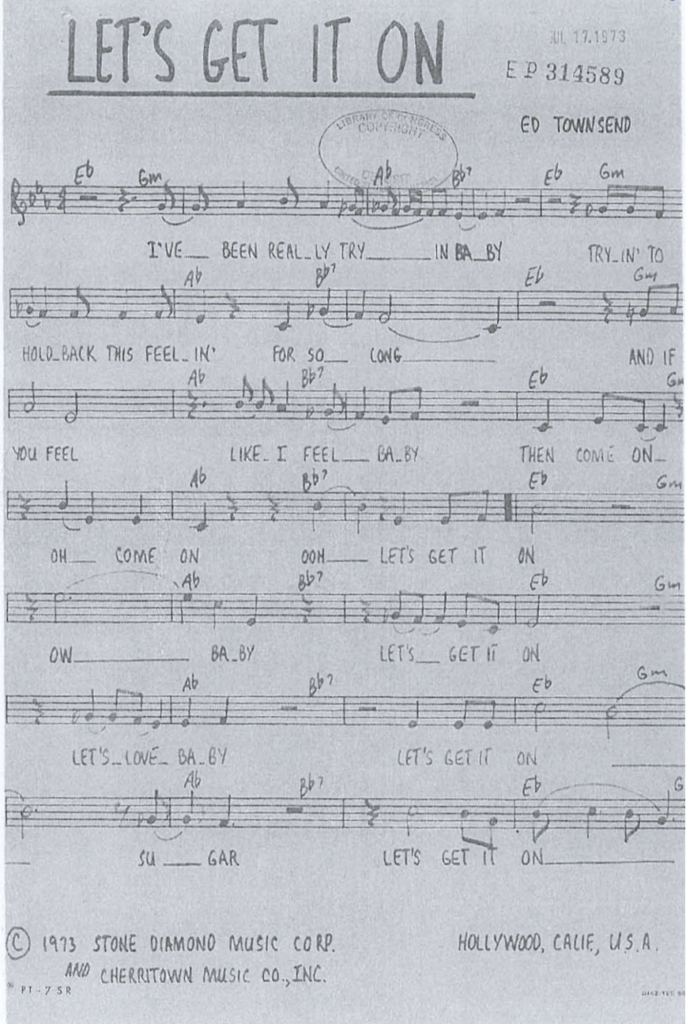

Under the 1909 Copyright Act, registration of a deposit copy was required, and audio recordings were not allowed to be filed, which meant the copyright protection was strictly limited to the sheet music for Let’s Get It On. As noted in the court order from March 2020, “The scope of the copyright is limited by the deposit copy”, and the deposit copy “defines precisely what was the subject of copyright”. The sheet music in the deposit copy looks like this (excerpt from the plaintiff’s submission).

The real issue of the case comes down to a more specific question, as nicely put by Louis Tompros, a lecturer on law at Harvard and partner at the WilmerHale Boston office: “[a]re the protected aspects of ‘Let’s Get It On’, as embodied in this deposit copy of the sheet music, similar to ‘Thinking Out Loud’?”

The Comparison

After understanding the copyright subject of Let’s Get It On, it is now meaningful to compare the elements of these two musical works. As mentioned earlier, the comparison is limited to the sheet music of Let’s Get It On filed with the Copyright Office, which, according to Lawrence Ferrara, the defendant’s expert, includes only “the composition’s key, meter, harmony (i.e., chord progression), rhythm, melody, lyrics and song structure”. It does not include “percussion/drums, bass-guitar, guitar, Marvin Gaye’s vocal performance, horns, flute, piano, strings, or any of the performance elements, such as the tempo in which to perform the composition, contained in the [Let’s Get It On] Recording.”

Plaintiff’s Arguments

The plaintiff argued that Thinking Out Loud copied melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic elements from Let’s Get It On (see plaintiff’s complaint, plaintiff’s response to defendant’s Rule 56.1 statement in 2018, and Alexander Stewart’s report). Key points include:

- Melody:

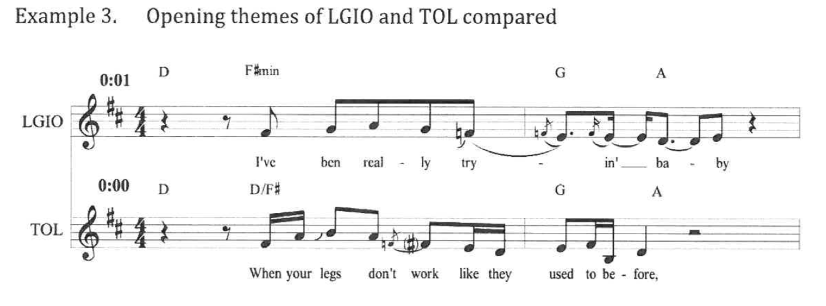

- The opening phrases of both songs have a similar length and overlap the bar line, starting on the same beat (See Example 3, extracted from Alexander Stewart’s report. (Iris note: although it is not exactly the same as the sheet music in Let’s Get It On’s deposit copy.)). The pitch sequences are:

- Let’s Get It On: 345432212

- Thinking Out Loud: 35653212361

- The opening phrases of both songs have a similar length and overlap the bar line, starting on the same beat (See Example 3, extracted from Alexander Stewart’s report. (Iris note: although it is not exactly the same as the sheet music in Let’s Get It On’s deposit copy.)). The pitch sequences are:

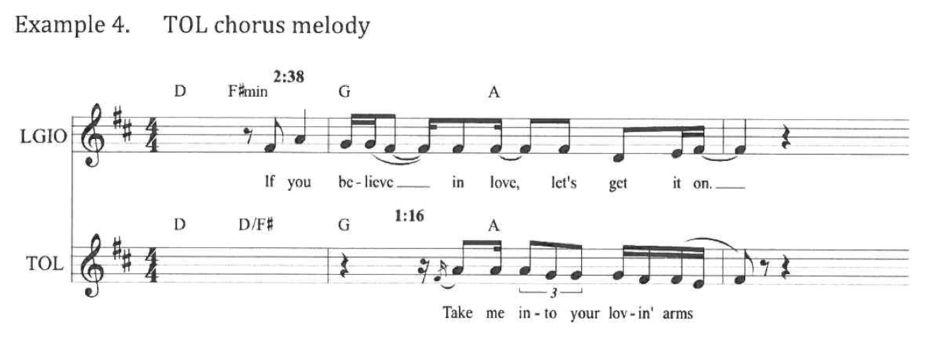

- For the chorus (see Example 4 extracted from Alexander Stewart’s report), the pitch sequences are:

- Let’s Get It On: 35443333123

- Thinking Out Loud: 35554443323

- Harmony:

- For the first 24 seconds of Thinking Out Loud, the chord progressions are identical to Let’s Get It On, and for more than 70% of Thinking Out Loud, the progression is “extremely similar”.

- The I-iii-IV-V chord progression was uncommon before Let’s Get It On, appearing in only about a dozen pre-1973 songs, out of hundreds of thousands of songs.

- Harmonic Rhythm:

- The harmonic rhythm in Let’s Get It On is a four-chord progression where the second and fourth chords are anticipated. This rhythm is identical to that in Thinking Out Loud.

Defendant’s Response

The defense countered these points (see defendant’s response and Lawrence Ferrara’s declaration in July 2018, declaration in September 2018, and report), arguing that:

- Melody:

- For the opening phrase, only 3 of 11 pitches in the opening phrase of Thinking Out Loud match the deposit copy of Let’s Get It On.

- For the chorus, only 5 of 11 pitches match in order.

- Harmony:

- While Let’s Get It On uses a I-iii-IV-V progression, Thinking Out Loud employs multiple progressions, including this one. However, this progression is common and found in elementary guitar method books.

- Harmonic Rhythm:

- Both songs use two chords per bar with anticipated second and fourth chords, but this technique predates Let’s Get It On, is not unique, was used in songs that predate Let’s Get It On, and is included in a guitar chord method book.

Court Rulings

The March 2020 court order acknowledged that that “[t]he Gaye sound recording contains many elements: percussion/drums, bass-guitar, guitars, Gaye’s vocal performances, horns, flutes, etc., which do not appear in the simple melody of the Deposit Copy. These additional elements – at least some of which appear in Thinking out Loud in more or less similar form – are not protected by copyright, because they are not in the Deposit Copy.”

The August 2020 court order further established that the chord progression and harmonic rhythm of Let’s Get It On are common techniques. Thus, the plaintiff’s expert could not claim the uniqueness of the chord progression and harmonic rhythm at trial but could testify to similarities in vocal melodies.

The jury verdict on 4 May 2023, found that the defendant independently created Thinking Out Loud and thus did not infringe the copyright of Let’s Get It On. The judge ordered the complaint to be dismissed.

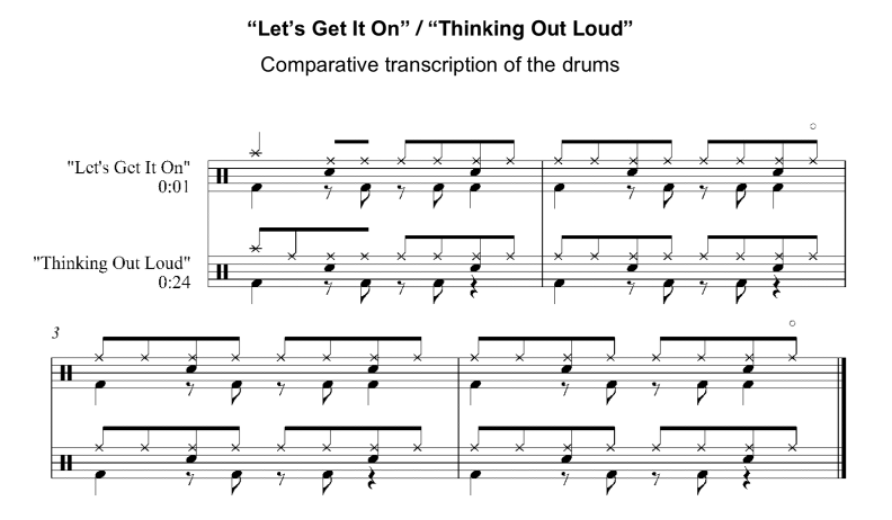

Personal Observation on Drum Patterns

Not relevant to the case decision (since the drum is not in the sheet music of the deposit copy of Let’s Get It On), but as an amateur drummer, I noticed the drum comparison in both experts’ reports out of curiosity. Here, I’ve extracted a section from Lawrence Ferrara’s report. It’s clear that the drum patterns are indeed very similar, but it’s also a very common pattern, especially the one in Thinking Out Loud, which appeared in my first few drum lessons.

Conclusion

So, to answer the question ‘Did Ed Sheeran copy Let’s Get It On?’ – based on the court ruling, the answer is no. While this case has not established groundbreaking legal principles, it provides musicians some relief that they won’t easily infringe on prior works’ copyrights, unlike in the earlier Blurred Lines case.

Disclaimer

Disclaimer: As a non-expert in U.S. law, I am writing this article purely out of personal interest and opinion. None of it should be interpreted as legal advice in any way.